All of us who have cared for patients living with dementia, know this progressive neurodegenerative disease steals memories, identities, and livelihoods. It often starts with mild, barely perceptible symptoms, making it hard to recognise what is happening, and it usually takes years to get a diagnosis. The main factor contributing to its development is age. As ageing populations are a worldwide reality, dementia is having a large social and economic impact.

People with dementia have problems with short-term memory, such as keeping track of a purse or wallet, paying bills, planning and preparing meals, remembering appointments, traveling out of the neighbourhood, etc. This worsens with time and people become more and more dependent on family and friends. This can go on for ten, fifteen years, or more. Alzheimer Disease International [1] and WHO [2] report it is one of the most expensive diseases with estimated socioeconomic costs topping $820bn each year; a third of care costs are from informal care.

Families usually adapt their lifestyles to members with dementia. There is the added complexity that much of this family care is provided by ‘sandwich’ generations who work as well as care for elderly family members and children. This is why it is so important to help people with dementia to be as autonomous as possible. Greater autonomy helps families worry less and facilitates social and health care delivery.

As dementia progresses, there are on average three people caring for one patient. In such a context, the term ‘living with dementia’ extends beyond the patients themselves, it involves their families and (in)formal carers. Research in this field has produced evidence on how to slow down the progression and fortunately, we also have different interventions and drug testing underway [3].

Emerging technologies are allowing communities to provide support. With new technologies, patients can be empowered to stay confident and independent. When necessary, modules that measure health parameters give professionals from the social and health care sectors remote access to patient dataand enable them to approach to the patient at the personalised level. Early interventions are beneficial for patients and their families, as well as to relieve the work and save the time of care systems professionals [4].

“Something that’s really important is to help people understand the level at which we want to be engaged. We still want to have social activities.”

– Anonymous Alzheimer’s patient

TeNDER will contribute to this research field by engaging key actors in the sector and leverage innovation to provide a concrete set of services to empower senior citizens in their daily activities. Moreover, the project will provide care institutions, professionals and authorities dedicated tools that could help them strengthen the management processes, as well as promote a framework for implementation and adoption. Ethics, and the integrity and privacy of all participants are key priorities as well.

In the context of COVID-19, all TeNDER partners – particularly partners who work directly with patients – have taken the necessary precautions to ensure the safety of vulnerable populations, patients, carers and health professionals. Spominčica – Alzheimer Slovenia, Servicio Madrileño de Salud,Asociación Parkinson Madrid, Schön Klinik and the University of Rome – Tor Vergata are currently implementing national and international COVID-19 health protocols (follow the links above to learn more).

For more information on the impact of COVID-19 measures and on international guidelines, here are some additional external resources for vulnerable populations:

FACTS ABOUT DEMENTIA

“Some days there won’t be a song in your heart. Sing anyway.” – Emory Austin

The field of dementia care has changed beyond recognition in the last 30 years. In 1987 dementia was supposed to be a rare condition. It was barely spoken about and was seen as an insignificant part of older people’s psychiatric care [7]. Today, more than 10 million Europeans are diagnosed and living with different forms of dementia. The time needed for informal care is estimated at 82 billion hours and 71% of these hours are supplied by women.

Women make up the largest proportion of the professional care workforce in dementia care[8]. Furthermore, the number of people with dementia is still probably underestimated. We can see different interpretations of cognitive impairment and dementia due to differences in health structures, that affect diagnoses and treatments.Patients with mild cognitive impairment or early-stage dementia remain outside clinical settings and most patients are not diagnosed in a timely manner, or not diagnosed at all [9].

Early diagnosis is a crucial step in accessing care and support for a person with dementia. With a proper diagnosis, family members and carers can have timely access to education, training and support programmes. Being aware of these facts, different support opportunities can drive the decision to seek a diagnosis and help prolong the autonomy of people.

ON LIVING WITH DEMENTIA

«It occurred to me that at one point it was like I had two diseases – one was Alzheimer’s, and the other was knowing I had Alzheimer’s.» – Terry Pratchett

I was invited to share my story about how my life has changed since my diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. I am pleased that my thoughts and positive attitude towards life were so well-received. I was told that I literally gave the attendees goosebumps! I try to always be open-minded and optimistic and to see the future in the brightest way possible. In my introduction, I told participants how I coped with the diagnosis and managed to re-organise my daily routine in order to live life to the fullest. I stressed that nothing has made me happier than realising what great friends I have.

Even though orientation is still the biggest challenge, on an everyday basis I continue with my leisure time activities, just as I always have done – playing tennis, ping pong, editing magazines, hiking, painting, and gardening. Currently, I am more worried, due to changes in my medical therapy, but I remain passionate about all the things I love. I gave the students a take-home message that I believe we all should take into account: “Even with dementia life is still beautiful” (Tomaž Gržinič) [10].

Don’t argue

Accept the situation

Nurture yourself

Creative problem-solving

Enjoy the moment!

As a person’s dementia develops, it is likely to have an impact on their ability to carry out certain activities. And here new technology can also help when managing the time, connections and planning. Meaningful activities such as taking a walk, cooking or painting can help preserve dignity and self-esteem. Some of the most beneficial activities can be simple, everyday tasks such as setting the table or folding clothes. They can help a person with dementia feel connected to normal life and can maximise choice and control. Some activities offer an emotional connection with others.

Throughout my caregiving journey, there were many moments of laughter, tears, frustration, sorrow and happiness, and I worked at incorporating them all into my repertoire. Some moments stand out as very special — like the time my husband who had not spoken for almost a year, replied, “You are the love of my life,” when I asked him if he knew who I was. It is these moments that kept me going.

Looking back, I think caregiving was one of the most difficult things I’d ever done. And as I watched the days turn into months, and then into years, I learned how to pace myself, how to reach out and ask and receive help. This did not occur overnight, but with lots of trial and error. Another thing I did that was invaluable was to join a support group. This in itself was a lifesaver and a source of comfort and socialisation. Fellow travellers make the best companion on the caregiving journey (Susan Miller) [11].

DEMENTIA IS NOT A SINGLE DISEASE

Dementia is not a single disease; it’s an umbrella term — like heart disease — that covers a wide range of specific health conditions. Diseases grouped under the umbrella term “dementia” are caused by abnormal brain changes. These changes trigger a decline in thinking skills, also known as cognitive abilities, severe enough to impair ones’ daily life and independent living. They also affect behaviour, feelings and relationships [5].

Dementia is caused by damage to brain cells. The brain has many distinct regions, each of which is responsible for different functions (for example, memory, judgment and movement). When cells in a particular region are damaged, that region cannot carry out its functions normally. This damage interferes with the ability of brain cells to communicate with each other. When brain cells cannot communicate normally, thinking, behaviour and feelings can be affected. Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia are highly prevalent, stressful, and challenging to manage.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia (60% – 80% of the cases). Besides age being a major risk factor, other risk factors include unhealthy lifestyles and vascular, metabolic, and nutritional risk factors [6].

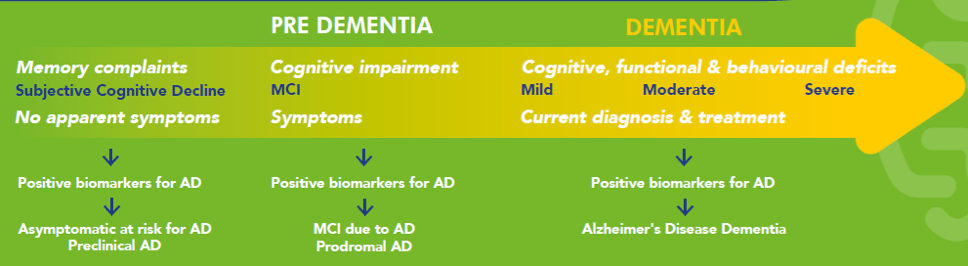

Figure: Understanding the phases of pre-dementia and dementia (MOPEAD project publication)

Older adults often have some decline in memory like difficulties with reasoning, memory, attention, language, but some have the perception that they experience changes that go beyond normal ageing. In this case, we speak about subjective decline that needs to be confirmed by a formal examination.

People with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) – have problems with their memory or cognitive function serious enough to be noticeable with neurological tests. At this stage, it is very important, to recognise the problems and to help the person to stay autonomous as long as possible, to manage lifestyles and seek the doctor advice.

Mild dementia due to AD – People may experience memory loss of recent events, may have an especially hard time remembering newly learned information and ask the same question over and over. At this stage, people have increasing trouble finding their way around, even in familiar places.

Moderate dementia due to AD – people grow more confused and forgetful and begin to need more help with daily activities and self-care. These difficulties make it unsafe to leave those in the moderate dementia stage on their own.

Severe dementia due to AD – at this stage, the disease has a growing impact on movement and physical capabilities. They require total daily assistance with personal care [12].

- Available at: https://www.alz.co.uk/research/world-report-2015

- Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia

- Available at: https://www.alzheimer-europe.org/Research/Clinical-Trials-Watch

- OECD Policy Brief. Renewing priority for dementia: Where do we stand? Paris: OECD Publishing, 2018. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/Renewing-priority-for-dementia-Where-do-we-stand-2018.pdf

- Available at: https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/

- Rodríguez-Gómez O, Rodrigo A, Iradier F, Santos-Santos MA, Hundemer H, Ciudin A, Sannemann L, Zwan M, Glaysher B, Wimo A, Bonn J, Johansson G, Rodriguez I, Alegret M, Gove D, Pinó S, Trigueros P, Kivipelto M, Mathews B, Ciudad A, Ferreira D, Bintener C, Gurruchaga M, Westman E, Belger M, Valero S, Maguire P, Krivec D, Kramberger M, Simó R, Garro IP, Visser PJ, Dumas A2 Georges J, Jessen F, Winblad B, Shering C, Stewart N, Campo L, Boada M; MOPEAD Consortium. “The MOPEAD project: Advancing patient engagement for the detection of ‘hidden’ undiagnosed cases of Alzheimer’s disease in the community.” Alzheimer’s & Dementia; 2019; 15 (6): pp. 828-839

- Dementia: Reflections 1987-2017, by Professor Dawn Brooker Available at: http://www.jkp.com/jkpblog/2017/05/dementia-field-changes-30-years/

- Available at: https://www.alz.co.uk/women-and-dementia

- Barnett JH, Lewis L, Blackwell AD, Taylor M. Early intervention in Alzheimer’s disease: a health economic study of the effects of diagnostic timing. BMC Neurolology (2014; 14:101). doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-14- 101.

- Available at: https://www.alzheimer-europe.org/News/Living-with-dementia/

- Available at: https://www.caregiver.org/walks-walk-and-talks-talk

- Available at: https://www.mayoclinic.org/

Another principle, that of purpose limitation, requires that personal data shall be collected for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes and may not be processed further in a manner incompatible with the original purpose. Moreover, according to the principle of data minimisation, no more personal data shall be collected than what is necessary for the realisation of the purpose for which they are processed. For example, collecting data that is not strictly necessary for the realisation of the TeNDER project would breach the data minimisation principle.

Another principle, that of purpose limitation, requires that personal data shall be collected for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes and may not be processed further in a manner incompatible with the original purpose. Moreover, according to the principle of data minimisation, no more personal data shall be collected than what is necessary for the realisation of the purpose for which they are processed. For example, collecting data that is not strictly necessary for the realisation of the TeNDER project would breach the data minimisation principle.

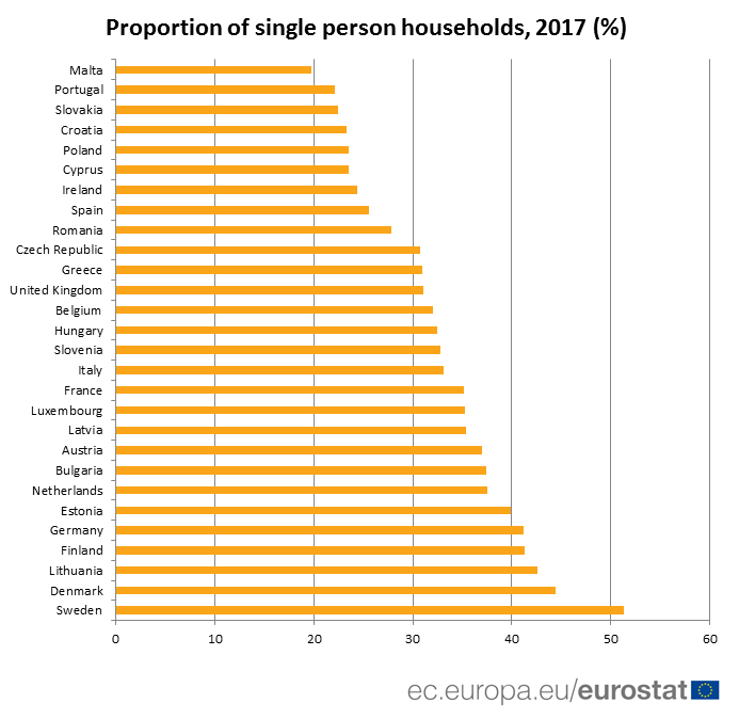

“Our bodies see loneliness as a mortal threat. When we’re alone, there’s no one to help us fight off that saber-tooth tiger or the hostile war party from the next village. Sensing that we are isolated and at risk, our bodies ramp up their defences in anticipation of the wounds and infections to come. It was a pretty good survival tactic thousands of years ago. In the modern world, though, it’s killing us.” [3]

“Our bodies see loneliness as a mortal threat. When we’re alone, there’s no one to help us fight off that saber-tooth tiger or the hostile war party from the next village. Sensing that we are isolated and at risk, our bodies ramp up their defences in anticipation of the wounds and infections to come. It was a pretty good survival tactic thousands of years ago. In the modern world, though, it’s killing us.” [3]

You know that your neighbour is part of the risk group but you have never talked to him or her before? What if you leave a message in their letterbox or in front of the door, proposing to go grocery shopping for them or taking their dog for a walk.

You know that your neighbour is part of the risk group but you have never talked to him or her before? What if you leave a message in their letterbox or in front of the door, proposing to go grocery shopping for them or taking their dog for a walk.