For most of us, rich daily activities are a fundamental component of our lives and also our identities. They help shape and validate our plans, values, motivations, beliefs, connections to others, and ideas of self-worth. Therefore, it might be inconceivable to think of our lives and identities devoid of much movement and activity. However, people with dementia might experience exactly this – a deterioration in their ability to plan for and execute daily living activities.

We dedicate this text to those who want to learn more about how this occurs, and the support mechanisms that might stall this process and mitigate the negative consequences of the tendency toward inactivity.

Dementia is a syndrome, which is a range of signs and symptoms that are caused by a number of diseases. It is associated with the progressive loss of functions, such as organisation and reasoning skills, orientation in place and time, regulation of emotions, speech, memory, etc.

One of the outcomes and a major symptom of dementia is a progressive loss of ability to perform daily activities.

Therefore, for a person with dementia, many of the activities that were feasible and “easy to do” before the onset of symptoms, may become more laborious and the goals less attainable. We often see an excessive overall reduction of daily life activities – including those which are still feasible despite the presence of some specific barriers. This is due to a lack of motivation and an inability to plan for and initiate activities.

In addition, a person with dementia may be less prone to experiencing pleasure (anhedonia) which will make it less likely for them to actively engage in activities they previously enjoyed. And due to changes in functional abilities when insight is still present, a person may become distressed when they experience difficulties completing tasks, especially those which appeared undemanding or even effortless before the onset of disease. This may depress their motivation for further action and discourage other attempts.

Therefore, even activities, which are well attainable by the person with dementia based on his/her remaining skills and abilities, may be greatly reduced unless we provide adequate encouragement and support.

Despite the usual or “natural” tendency of the person with dementia to greatly diminish their activity throughout the day, such activity is in fact vital for slowing the progression of symptoms and supporting his/her well-being.

Involvement in rich everyday activities supports cognition, motor skills (coordination, balance), and general mood. In addition, it may promote healthier sleep patterns.

Why does the quality of sleep matter?

As people get older, their sleep may change due to effects of ageing. Many of these changes occur due to alterations in the body’s internal clock. The section of the brain which regulates our clock (suprachiasmic nucleus, SCN) control the 24-hour daily cycles, called circadian rhythms. These circadian rhythms influence daily cycles, such as when we get hungry, when the body releases certain hormones, and when we feel sleepy or alert. The SCN receives information from the eyes, and light is a cue for maintaining the circadian rhythms.

Alzheimer’s disease (the most common cause of dementia) often changes a person’s sleeping habits. Some people with Alzheimer’s disease sleep too much; others don’t sleep enough. Some wake up many times during the night; others wander or yell at night. Sleep disturbances and Alzheimer’s disease often go hand in hand. A decrease in the cellular activity of the dedicated region in the brain is common, and cells may be damaged due to the disease as well. The result of this is that patients are often unable to follow a 24-hour sleep-wake cycle. In addition to this, dementia is associated with transformations of sleep structure.

Specific sleep stages

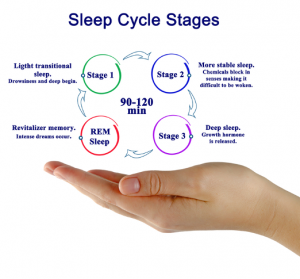

When we sleep, our bodies cycle through a series of sleep stages, starting with light sleep (stages 1 and 2), followed by deep sleep (stage 3 or slow-wave sleep), and later by dream sleep (also called rapid eye movement or REM sleep).

Slow-wave sleep and REM sleep are the critical stages for the sleep to restore the body and the mind. REM is the stage when dreaming occurs. During REM there is increased activity in the limbic structures involved in memory and emotional regulation, whereas there is less activity in the frontal brain systems involved in analytic thinking. REM plays a pivotal role in memory and other cognitive functions. Other sleep stages are also associated with memory. Specific sleep stages are associated with different types of learning. [1]

People with dementia spend less time in slow-wave sleep and REM sleep and more time in the earlier stages of sleep than their peers. This reduction of deep sleep and REM sleep can worsen as dementia progresses. [2]

The consequences of this are interrupted sleep, wakefulness, wandering during the night, as well as day-time tiredness, sleepiness, and irritability. “Sundowning” is another phenomenon in which individuals with dementia experience increased agitation later in the day and in the evening. The symptoms of sundowning include confusion, anxiety, wandering, and yelling. Additionally, obstructive sleep apnea is more common in people with Alzheimer’s disease than in the general population of older people. This potentially serious sleep disorder causes breathing to repeatedly stop and start during sleep.

[1] Margaret O’Connor, PhD, ABPP, Harvard Health Blog » Aging and sleep: Making changes for brain health – Harvard Health Blog.

[2] https://www.sleepfoundation.org/mental-health/dementia-and-sleep

To promote better sleep it is important to keep the following in mind:

- Maintain a regular schedule. Create a bedtime routine that involves quiet, soothing activities before bed. Television and electronic devices can be stimulating and emit blue light that interferes with sleep, so try avoiding these activities before bed;

- Limit naps to no longer than 30 minutes;

- Add light exposure. Light is a key regulator of circadian rhythm, so if possible, getting natural light during the day can help with sleep at night. If access to natural light is limited due to weather or other factors, indoor bright light therapy may help;

- Avoid stimulants like caffeine, alcohol, and nicotine if possible;

- Treat pain and sleep disorders;

- Set a peaceful mood in the evening. Help the person relax by reading out loud or playing soothing music. A comfortable bedroom temperature can help the person with dementia sleep well. Create a calming bedroom environment: A dark, quiet, comfortable bedroom promotes sleep. Some people with dementia benefit from having well-loved objects near their beds. If total darkness is not calming, add dimmed night lights to create a sense of security.

A very important part of the day, which influences sleep, is, of course, the active part. We can significantly manage sleep quality (and consequently some potential problems during wakefulness as well) by supporting the appropriate daily activities. It is vital to understand that the day- and nightlife of a person are interconnected.

Encouraging daily activities, especially those which increase exposure to sunlight and physical activity (such as an afternoon walk in the park) will improve the circadian rhythm and promote late-night tiredness.

However, the implementation of activities must be done carefully, to not overburden the person with dementia and to avoid unnecessary distress. Below we outline some suggestions about the types of possible activities and guidelines for successful implementation. Above all, it is vital to ensure that the activities we choose are adapted to the wants, needs, and abilities of the person in question.

Some ideas for activities at home:

- fold towels;

- put dishes in the cupboards;

- buy beans of different colors and asking the person to organise them by color;

- make the bed together;

- go for walks;

- ask them to keep company to a pet or to entertain children;

- brush teeth;

- when making food, ask them to stir the food while you cut the vegetables;

- solve puzzles and play card games: in the plethora of card games, we choose the ones which are attractive to the person with dementia. These choices may change through time: at one point, Solitaire, Uno, and Donkey might be the best choice and later on, we can make up rules and goals, such as stacking the cards by signs, values, or colors;

- arrange flowers, ornaments, or personal photos;

- arrange for them to have tea with a friend.

Guidelines for implementing the activities:

- Communicate the activity in simple language, maintain eye contact, use your body to support your speech, and remain calm if the person resists or reacts adversely.

- Be encouraging during the activity; invite the person to participate, praise them during and after the activity. When a person is not interested in participating, we do not explain why they should do it. Try waiting for a bit and invite them again later, perhaps with a differently formulated invite.

- It is advisable to implement activities regularly, at roughly the same time. Routine is recommended to avoid distress by presenting too many novel stimuli, which may overwhelm a person with dementia.

- Note that caution is due when choosing the complexity of the task. As abilities deteriorate, adapt the difficulty of the task and fragment the tasks into smaller and smaller consecutive tasks. For example, an activity involving cooking might encompass preparing a full meal, such as spaghetti and sauce in the initial stages of dementia. Later on, the person will cook pasta, but we will prepare the sauce. When we notice that the person is having trouble cooking pasta, we will divide the activity further. We will ask them to fill the pot with water and insert pasta. Even later, we proceed with fragmenting the tasks, such as: open the drawer / find the blue pan / hand me the blue pan.

- Pick or adapt activities so that the goal is always reached.

- Dissect the activity based on current abilities and moods.

- When choosing an activity, try to think of what the person might prefer based on their usual likes and dislikes (gardening activities might fit ones and technically oriented activities, such as sorting clock mechanisms may fit others). Even preferences are prone to change as the disease progresses.

- Avoid dangerous activities or take necessary precautions.

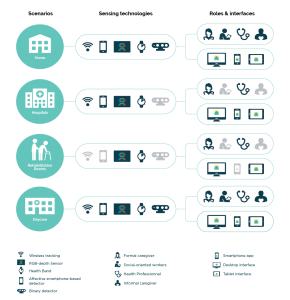

The TeNDER system, which integrates several sensors, is as a whole designed to assist the patients, caregivers, and professionals in coping with issues associated with dementia and several other conditions. Amongst several other functionalities, the system may assist in supporting the activity of the patient as well.

The TeNDER system, which integrates several sensors, is as a whole designed to assist the patients, caregivers, and professionals in coping with issues associated with dementia and several other conditions. Amongst several other functionalities, the system may assist in supporting the activity of the patient as well.

- For example, the carer may not have the opportunity to be present at all times to initiate and support all activities throughout the day. The TeNDER system may help initiate daily activities like going outdoors when remaindered, initiate housework (tasks can be divided into simple parts to follow), taking exercise, reading a book, meeting with people…

- The system may be used by the carer to communicate instructions, check the progress of a person they are caring for, and also motivating him/her. Meanwhile, the recipient of care may be able to communicate back and the carer may have insights into obstacles and progress through TeNDER.

- Note, that the social aspect of daily activities is vital for an activity to be beneficial. Therefore, technology should serve as support and not as a substitution for socialising.

- In addition to this, the calendar function may be used so that the carer experiences fewer obstacles when following up with the routine and daily activities of a person. They may plan for activities and list ideas for future activities.

- Data from the TeNDER sensors may assist the professional when formulating advice for personalised activities. For example, when sleep disturbances are indicated by a sleep sensor a professional might decide that a regime of light exercise and physical activity will assist in reducing symptoms. A health professional might suggest activities to input in the calendar. The calendar function will remind the patient to exercise regularly and the caregivers might be able to verify the completion of activity in real-time.

References:

Alzheimer’s Association (2021). Daily care. https://www.alz.org/help-support/caregiving/daily-care/activities

Dobbs, D., Munn, J., Zimmerman, S., Boustani, M., Williams, C. S., Sloane, P. D., & Reed, P. S. (2005). Characteristics Associated With Lower Activity Involvement in Long-Term Care Residents With Dementia. The Gerontologist, 45(suppl_1), 81-86.

Engelman, K., Altus, D., & Mathews, R. (1999). Increasing Engagement In Daily Activities By Older Adults With Dementia. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 32(1), 107–110. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1999.32-107

Fry, A. (2021). Dementia and Sleep.

LeBlanc, L. A., Cherup, S. M., Feliciano, L., & Sidener, T. M. (2006). Using Choice-Making Opportunities to Increase Activity Engagement in Individuals With Dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementiasr, 21(5), 318-325.

LeBlanc, L. A., Raetz, P. B., Baker, J. C., Strobel, M. J., & Feeney, B. J. (2008). Assessing preference in elders with dementia using multimedia and verbal pleasant events schedules. Behavioral Interventions, 23(4), 213-225.

O’Connor, M. (2019). Aging and sleep: Making changes for brain health. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/aging-and-sleep-making-changes-for-brain-health-2019031116147

Volicer, L., Simard, J., Pupa, J. H., Medrek, R., & Riordan, M. E. (2006). Effects of continuous activity programming on behavioral symptoms of dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 7(7), 426-431.

https://universityhealthnews.com/media/sleep-stages-sleep-cycle.jpg; accessed 23.4.2021, Sleep Foundation – A OneCare Media Company